Picture this: A provincial ministry launches a new digital service for business licensing. The platform is technically sound, passes all security requirements, and integrates with existing government systems. Six months later, call centre volumes haven’t decreased. Eighteen months later, the digital service is barely used. Two years in, there’s no budget to update content or fix emerging accessibility issues. The service quietly degrades while users revert to familiar channels. The team who built the service loses enthusiasm and morale. Leadership questions the value of digital investment. Users lose trust.

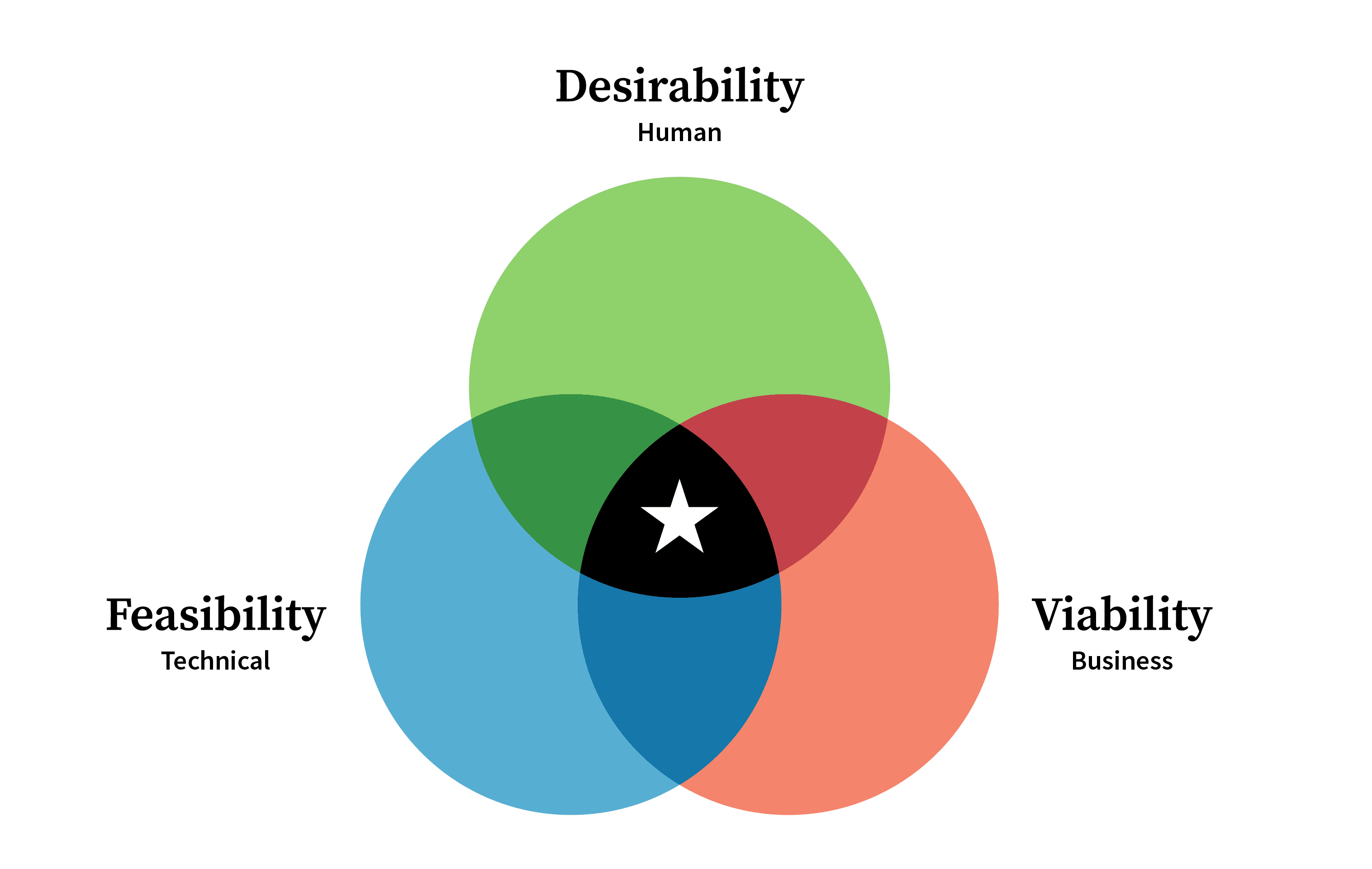

This pattern is common enough that most people working in public sector digital services will recognize it immediately. The project addressed feasibility—the technical and policy requirements—but skipped two critical questions: What do users actually need, and can we sustain this over time?

These three lenses—desirability, feasibility, and viability—form the foundation of effective service design. But the reality of Agile service design, especially in the public sector, is about navigating continuous tension between these forces.

The three lenses defined

Desirability asks: What do people actually need and want? Desirability emerges from observing what people actually do, understanding their context and constraints, and identifying unmet needs they may not articulate directly. In public services, this includes fundamental equity considerations. Desirability isn’t “nice to have.” It’s foundational to service uptake and legitimacy.

Feasibility asks: Can we actually build, deliver, and validate that this works? This includes technical capability, organizational capacity, and policy constraints. In the public sector, feasibility often means navigating legacy systems, procurement rules, and interagency dependencies. But feasibility extends beyond the build phase. It includes a critical validation question: Can users actually accomplish what they need to? A service may be technically functional but fail completely if users can’t navigate it or complete required tasks.

Viability asks: Can we sustain this over time? This encompasses ongoing operational costs, staff capacity, training needs, and maintenance requirements. Viability means considering budget cycles, change management, content governance, and evolving user needs. It’s the most frequently overlooked lens, leading to the “build it and figure it out later” problem that haunts digital government initiatives.

Where public sector projects get stuck

Government projects frequently start with feasibility: What do our systems support? What does policy require? This constraint-first approach results in “solutions looking for problems” that are technically sound but see low adoption.

Desirability gets addressed through consultation, but often superficially. Teams gather requirements through surveys asking what people want, rather than observing what they do. The difference matters. People may say they want option A, but their behaviour reveals they consistently choose option B.

Viability is where projects most often fail. Common patterns include assuming existing staff will absorb maintenance without additional resources, launching without plans for responding to user feedback, and having no budget for improvements or updates. Services degrade, users lose trust, and organizations maintain zombie systems that don’t fulfill their purpose.

How human-centred design addresses all three

Human-centred design methodologies bring all three lenses into focus throughout a project lifecycle.

Desirability is addressed through research that reveals what people actually do, not just what they say. When we observe users in context—watching where they get stuck, what workarounds they’ve created—we discover needs they couldn’t articulate in a survey. Journey mapping makes these patterns visible across the end-to-end experience and accounts for diverse user groups, showing where services break down and where equity gaps exist.

Feasibility is addressed through collaborative design and validation. Service blueprinting makes the “backstage” visible—the operations, systems, staffing, and resources required to deliver a service. For example, a seemingly simple feature like “email notification” reveals dependencies on email servers, staff who respond to bounced messages, content governance for notification templates, and accessibility requirements for email formatting. Working alongside subject matter experts and technical teams from discovery onward ensures solutions are grounded in organizational reality. And critically, usability testing validates that users can actually complete their tasks.

Viability is addressed through operational planning embedded in service design. Mapping required resources in backstage swim lanes forces conversations about who will maintain this, how staff will be trained, and where ongoing budget will come from.

The Agile advantage is that teams revisit these lenses in cycles. Early prototypes test desirability with users, usability through task completion testing, technical feasibility with development teams, and viability with operations staff—all before major investment. Each sprint provides an opportunity to adjust the balance and make tradeoffs explicit.

Viability through integrated teams: DriveBC modernization

The DriveBC platform—BC’s most-trafficked government website—required more than a technical rebuild. It needed a team capable of sustaining it long-term. Rather than the traditional “vendor delivers and departs” model, we’ve worked as a unified team with Ministry staff for over two years. Our Project Manager introduced Agile practices while coaching the Ministry’s Product Owner and transitioning the Scrum Master role to government staff after six months. We didn’t just build features—we built capacity. Ministry staff were embedded in every sprint, contributing to backlog prioritization, user research, and technical decisions. The service blueprint we created together maps not only the user-facing platform but the operational workflows, CMS capabilities, and staff responsibilities needed to maintain accuracy during emergencies. When we eventually transition off, the Ministry team won’t be inheriting an unfamiliar system. They’ll be continuing work they’ve been leading all along.

Continuous navigation

The Venn diagram suggests a stable equilibrium. The reality is more dynamic. User needs evolve. Technology changes. Organizational capacity shifts. Budget realities intrude.

Effective service design in the public sector means building in the capacity to revisit these questions continuously, not just during initial development. It means establishing feedback loops, planning for iteration, and being honest about tradeoffs.

The question isn’t whether your service technically functions—it’s whether citizens will use it, whether they can successfully accomplish their goals with it, and whether your organization can sustain it five years from now. If you can’t answer yes to all three, you’re not alone. Many public sector projects struggle with at least one of these lenses. The good news is identifying which lens needs attention is the first step toward building services that work well—and keep working well.

Where is your current project on this map? Which lens needs more attention?