Recently, I worked with a higher education client to help their delivery team mature their design system capabilities. It wasn’t a surprise that passionate debates erupted over component prioritization.

“We need to start with the most-ubiquitous stuff first: the accordion. Isn’t that obvious? It’s the one component shared by all our departmental subsites.”

“No,” another group countered, “we need to start with the foundational stuff, like heading, links, and block quotes. That’s critical for brand cohesion.”

And of course, leadership had their own opinions. “The most strategically important component is our video carousel. We need that to tell our story and keep all the departments competing for homepage real estate happy.”

Why design systems matter

Design systems are meant to provide efficiency in design, using pre-assembled pieces instead of constantly reinventing elements. They offer tremendous benefits: users experience consistency and don’t struggle with endless learnability challenges; brands are reinforced through cohesive presentation; and development teams work faster with standardized components.

When implemented well, design systems cost less, create better experiences for users, and maintain brand integrity across digital touchpoints.

But when design systems struggle to achieve their full potential, it’s not because of technical shortcomings, but because organizations often focus on collections of components instead of what they actually need: frameworks for navigating competing priorities.

The often overlooked benefit of design systems: principles

Back to our component prioritization debate: different groups within the organization advocated for their own urgent needs, each with compelling justification.

The breakthrough came not from improved technical documentation or executive mandates, but from establishing design principles that acknowledged the underlying dynamics.

Great design principles acknowledge and address the invisible power dynamics of organizational change. More than brand-like guidelines, they’re the essential language that elevates technical components into strategic assets that deliver measurable value.

“Simple before complex, frequent before one-offs”

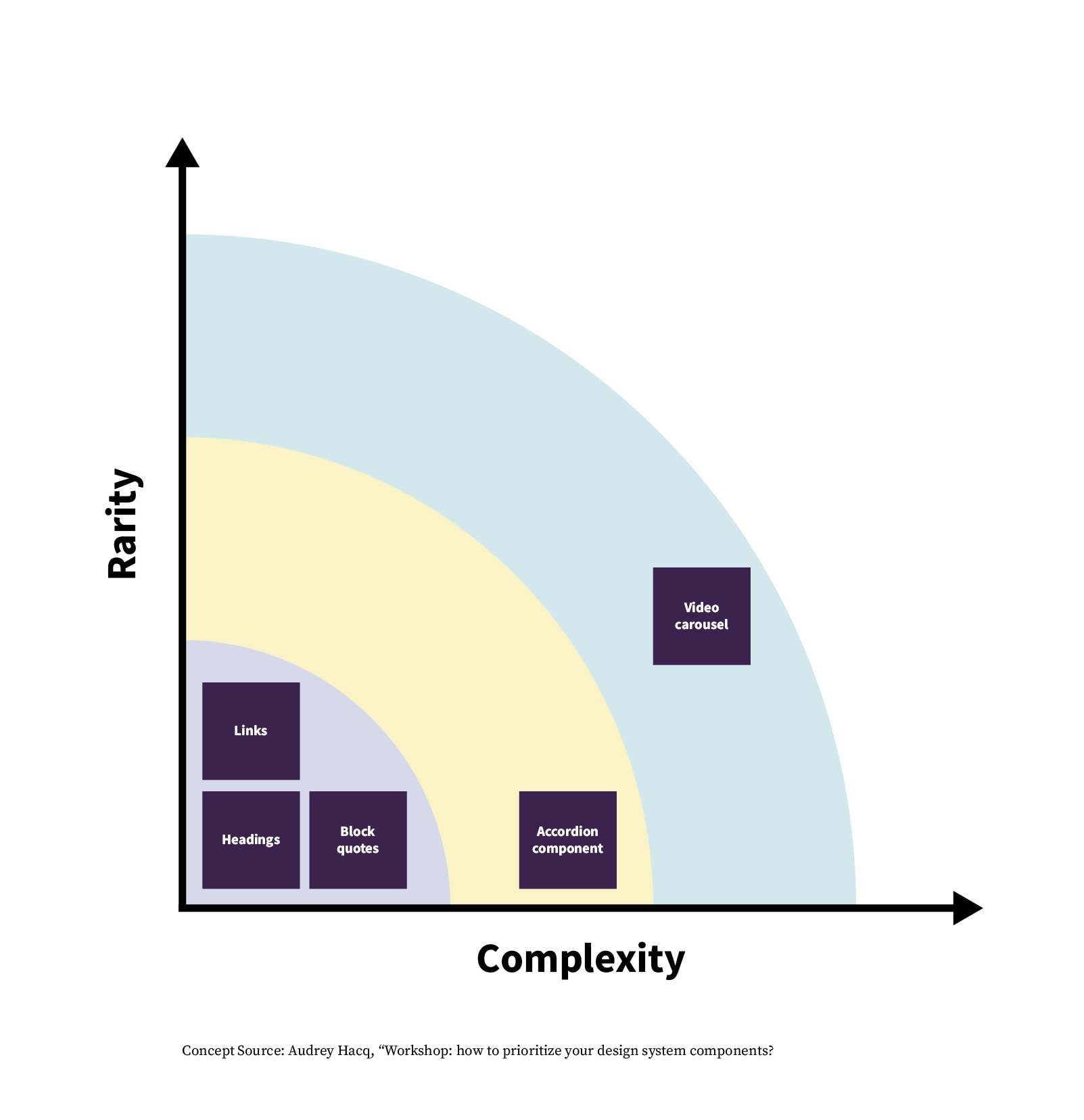

By adopting a principle from Nathan Curtis—one of the leading voices on all things relating to design systems—like “Simple before complex, frequent before one-offs,” these groups in the organization created a shared language that depersonalized prioritization. They could now plot components within a matrix defined by those two axes—complexity and frequency—and use that to prioritize components more effectively.

This wasn’t just about efficiency or personal preference. It was about creating legitimate grounds for saying “not yet” to stakeholders without appearing arbitrary.

What looked like a technical discussion about accordions versus quote blocks was actually a negotiation over departmental influence and resource allocation. The principles provided neutral territory for these negotiations.

Design principles are important decision making tools, if used well

Good design principles acknowledge and work within the reality of organizational priorities. And instead of just pretending that decisions are purely objective, empowering design principles create legitimate spaces for negotiating competing values.

When teams can navigate these negotiations efficiently, they deliver consistent experiences faster and with less duplication of effort—directly improving service delivery timelines and quality. Designers need to be able to make that connection—between business objective and design execution—and that’s where thoughtful, specific design principles come into play.

“Simplicity first, layer complexity as needed”

For example, a generic principle like “Be consistent” offers little navigational help. But a principle like “Simplicity first, layer complexity as needed” offers a more concrete tool for resolving the tension between flexibility and standardization—a strategic challenge disguised as a technical one. This approach ensures users encounter interfaces that meet their basic needs first, while allowing for appropriate complexity where it serves more advanced requirements—balancing accessibility with functionality.

Sadly, design principles are frequently expressed as esoteric quips that resemble aspirational statements framed on office walls or repeated in big bold letters in design conference presentations. What should be a powerful decision framework becomes more like an aesthetic or just corporate wallpaper.

Design principles are a communication tool

Principles should be used, debated, and refined over time. They grow stronger as teams apply them to real-world decisions.

Sign up for our newsletter using the form below to get our latest insights, case studies, and news delivered straight to your inbox.