The University of British Columbia (UBC) is a globally recognized leader in teaching, learning, and research, consistently ranking among the top five percent of universities worldwide. Maintaining this prestigious reputation requires consistent, compelling storytelling across all digital touchpoints—a responsibility that falls to UBC’s Brand and Marketing (BAM) team.

BAM identified the need for a design system to improve brand consistency and service delivery efficiency across their marketing websites. But as they began the journey, they discovered the real barriers weren't technical—they were organizational.

When the real problem isn’t what you think it is

UBC’s Brand and Marketing department was struggling with inconsistent brand experiences across digital platforms, unclear governance structures, and inefficient collaboration between design and development teams. The symptoms were clear:

Duplication of effort and inconsistent execution. Teams were spending significant time “reinventing the wheel” for each project, with slightly different design implementations undermining brand consistency across subsites.

Decision-making paralysis. Multiple rounds of approvals and unclear authority were stalling projects. Team members felt lost in the ambiguity: “I don't know what's expected of me on the project or who to reach out to for questions.”

Cross-functional miscommunication. Design and development teams spoke different languages, with mismatched tools and varying domain expertise creating friction and misalignment.

Capacity constraints. The design system work was happening “off the side of their desks” rather than as a dedicated priority, making sustained progress difficult as daily demands took precedence.

While BAM initially approached OXD for help developing a design system, discovery revealed that governance and collaboration gaps were the real barriers holding them back.

Coaching through a safe-to-fail pilot

Rather than building the design system for them, we focused on coaching BAM’s teams to develop the capabilities they’d need to build and maintain it themselves. We worked through three distinct phases, using a hands-on pilot project as the vehicle for learning.

Phase 1: Discovery and alignment

We brought stakeholders together through workshops—including Future Backwards strategic planning—to surface different perspectives and agree on what success would look like.

We mapped outcomes at three time horizons. Working with the team, we connected daily activities to meaningful change: what would improve now (faster decisions, clearer roles), what would develop soon (a more useful design system), and what would eventually be possible (external teams creating on-brand work with minimal BAM support and a “happy, inspired, and excited” BAM team).

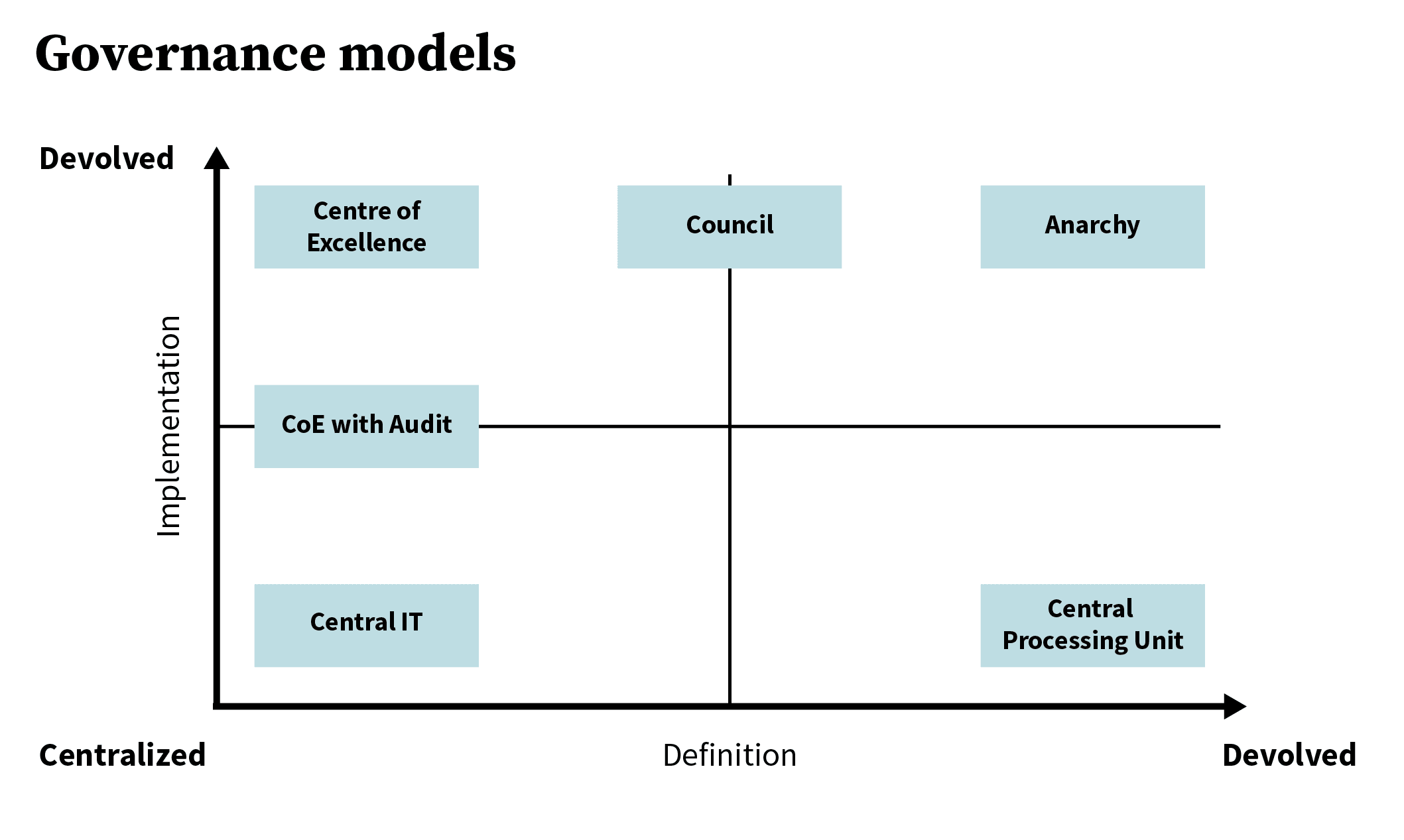

We taught design system fundamentals, covering how successful organizations structure their systems for the long term. This included exploring different governance approaches—from fully distributed teams to centrally controlled models—so BAM could understand their options.

Phase 2: Building structure and process

We reviewed their existing work. Looking at design and code across BAM’s properties, we helped the team spot inconsistencies and identify the best practices that could become their system’s foundation.

We helped BAM apply governance frameworks to their specific context. Working along the distributed-to-centralized spectrum, we mapped where they currently were and where they needed to be in order to suit their organization’s structure and culture.

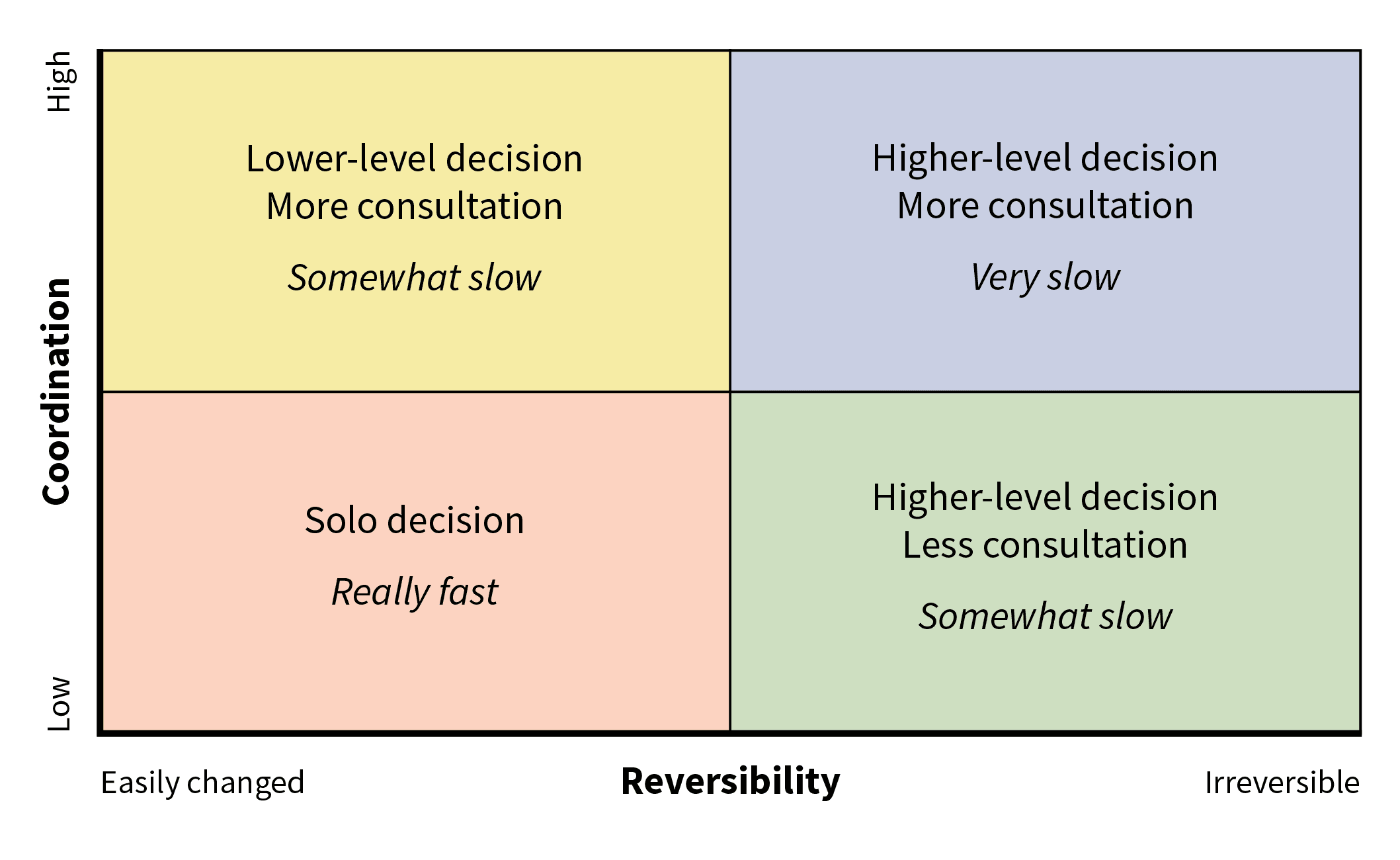

We taught the DICE decision-making framework to replace unclear authority with transparent roles: who Decides, who needs to be Informed, who should be Consulted, and who Executes. The key principle: push decisions as close to execution as possible.

We trained teams in agile practices—sprints, stand-ups, and retrospectives—establishing regular rhythms for collaboration and continuous improvement that would outlast any single project.

Phase 3: Learning through practice

We led a sprint-based pilot project where teams collaboratively built their first design system component. Starting with over a dozen prioritized components (headings, navigation, cards, colours, and more), they successfully completed one together. This proved their new ways of working actually worked—not just in theory, but in practice.

The pilot wasn’t about the deliverable. It was about creating a safe space to learn.

The ‘safe space’ of the pilot project allowed us to build a layer of trust that’s still serving us today. The practice of running regular sprint reviews and retrospective sessions in particular has helped us build greater empathy and trust across the team.”

Adrian Liem, Associate Director, Digital Solutions, Brand and Marketing, UBC

As neutral third parties, we mentored teams through real-world challenges, modeled effective practices, and created space for experimentation without the pressure of production deadlines.

Transformation through capability building

Through our coaching engagement, UBC BAM achieved measurable progress across their strategic goals.

Clear roles and faster decisions. Teams now know exactly who to consult and who decides. Projects no longer stall in multiple approval rounds. As one team member noted: “Decisions are considered earlier.”

A foundation for system growth. Teams understand the distinction between building the design system and building products that use it. They’ve developed working design principles, explored design tokens, and created processes for maintaining consistency while allowing appropriate flexibility.

Skills that spread beyond the project. While external teams aren’t yet using the system independently, BAM has established the processes, tools, and team dynamics to get there. More importantly, the skills they’ve developed are already “positively impacting other internal projects.”

Embedded collaborative practices. Weekly retrospectives are now standard. Sprint planning sessions and decision-making frameworks naturally identify which small “break-out meetings” are needed rather than defaulting to large, inefficient gatherings. Teams work with greater empathy and trust across disciplines.

Genuine team engagement. Team members are excited to collaborate and apply their new skills. The tools they’re using—stand-ups, retros, sprint planning—are described as “excellent” for moving work forward.

“The initial engagement and coaching has helped our teams come together and improved the way we interact. There is better and more open communication about needs and requirements from each team.”

—UBC BAM Team Member

“Sprint planning helped us determine what break-out meetings need to take place, which is something we never really worked out before. Break-outs involve one-to-three individuals rather than everyone.”

—UBC BAM Team Member

Building organizational capacity for the long term

BAM initially thought they needed a design system. What they really needed was a new way to practice governance and collaboration. By addressing these fundamentals first—through structured workshops, proven frameworks like DICE, design audits, and hands-on pilot experience—we equipped BAM with the capabilities to scale their design system work.

The transformation is systemic, not transactional. UBC moved from working in silos with unclear ownership to integrated cross-functional teams with transparent governance. They understand that a design system is a perpetual practice, not a one-time project—a commitment to iterative improvement that requires sustained investment. The path forward is clear. While completing their first component took 17 sprints as they learned new ways of working, future components will be faster. Most importantly, they’ve built the organizational muscle—the collaboration skills, governance structures, and team confidence—that will serve them far beyond the design system itself.